(Riza Afita Surya) History, Education, Art, Social Enthusiastic

Dear my sweetiest visitors, according to my satistic account. I've realized that you're not only from my country, i mean Indonesia. There's from many others country, well...i just wanna join with you. I wanna sahare anything with you, comin to twitter and go follow me. It will sums me up..just click "Rizasuya". Thanks for attention

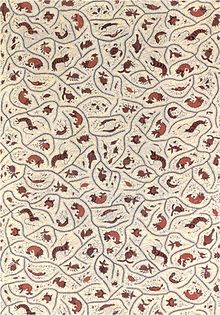

Batik (Javanese pronunciation: [ˈbate?]; Indonesian: [ˈbatɪʔ]; English: /ˈbætɪk/ or /bəˈtiːk/) is a cloth that traditionally uses a manual wax-resist dyeing technique.

Javanese traditional batik, especially from Yogyakarta and Surakarta, has special meanings rooted to the Javanese conceptualization of the universe. Traditional colours include indigo, dark brown, and white, which represent the three major Hindu Gods (Brahmā, Visnu, and Śiva). This is related to the fact that natural dyes are most commonly available in indigo and brown. Certain patterns can only be worn by nobility; traditionally, wider stripes or wavy lines of greater width indicated higher rank. Consequently, during Javanese ceremonies, one could determine the royal lineage of a person by the cloth he or she was wearing.

Other regions of Indonesia have their own unique patterns that normally take themes from everyday lives, incorporating patterns such as flowers, nature, animals, folklore or people. The colours of pesisir batik, from the coastal cities of northern Java, is especially vibrant, and it absorbs influence from the Javanese, Arab, Chinese and Dutch culture. In the colonial times pesisir batik was a favorite of the Peranakan Chinese, Dutch and Eurasians.[citation needed]

UNESCO designated Indonesian batik as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity on October 2, 2009. As part of the acknowledgment, UNESCO insisted that Indonesia preserve their heritage.[1]

Wax resist dyeing technique in fabric is an ancient art form. Discoveries show it already existed in Egypt in the 4th century BCE, where it was used to wrap mummies; linen was soaked in wax, and scratched using a sharp tool. In Asia, the technique was practised in China during the T'ang dynasty (618-907 CE), and in India and Japan during the Nara period (645-794 CE). In Africa it was originally practised by the Yoruba tribe in Nigeria, Soninke and Wolof in Senegal.[6]

Wax resist dyeing technique in fabric is an ancient art form. Discoveries show it already existed in Egypt in the 4th century BCE, where it was used to wrap mummies; linen was soaked in wax, and scratched using a sharp tool. In Asia, the technique was practised in China during the T'ang dynasty (618-907 CE), and in India and Japan during the Nara period (645-794 CE). In Africa it was originally practised by the Yoruba tribe in Nigeria, Soninke and Wolof in Senegal.[6]

In Java, Indonesia, batik predates written records. GP. Rouffaer argues that the technique might have been introduced during the 6th or 7th century from India or Sri Lanka.[6] On the other hand, JLA. Brandes (a Dutch archeologist) and F.A. Sutjipto (an Indonesian archeologist) believe Indonesian batik is a native tradition, regions such as Toraja, Flores, Halmahera, and Papua, which were not directly influenced by Hinduism and have an old age tradition of batik making.[7]

GP. Rouffaer also reported that the gringsing pattern was already known by the 12th century in Kediri, East Java. He concluded that such a delicate pattern could only be created by means of the canting (also spelled tjanting or tjunting; IPA: [tʃantɪŋ]) tool. He proposed that the canting was invented in Java around that time.[7]

Batik was mentioned in the 17th century Malay Annals. The legend goes when Laksamana Hang Nadim was ordered by Sultan Mahmud to sail to India to get 140 pieces of serasah cloth (batik) with 40 types of flowers depicted on each. Unable to find any that fulfilled the requirements explained to him, he made up his own. On his return unfortunately, his ship sank and he only managed to bring four pieces, earning displeasure from the Sultan.[8][9]

In Europe, the technique is described for the first time in the History of Java, published in London in 1817 by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles who had been a British governor for the island. In 1873 the Dutch merchant Van Rijckevorsel gave the pieces he collected during a trip to Indonesia to the ethnographic museum in Rotterdam. Today Tropenmuseum housed the biggest collection of Indonesian batik in the Netherlands. The Dutch were active in developing batik in the colonial era, they introduced new innovations and prints. And it was indeed starting from the early 19th century that the art of batik really grew finer and reached its golden period. Exposed to the Exposition Universelle at Paris in 1900, the Indonesian batik impressed the public and the artisans.[6] After the independence of Indonesia and the decline of the Dutch textile industry, the Dutch batik production was lost, the Gemeentemuseum, Den Haag contains artifacts from that era.

Due globalization and industrialization, which introduced automated techniques, new breeds of batik, known as batik cap (IPA: [tʃap]) and batik print emerged, and the traditional batik, which incorporates the hand written wax-resist dyeing technique is known now as batik tulis (lit: 'Written Batik'). At the same time Indonesian immigrants to Malaysia and Singapore brought Indonesian batik with them.

Depending on the quality of the art work, dyes, and fabric, the finest batik tulis halus cloth can fetch several thousand dollars and it probably took several months to make. Batik tulis has both sides of the cloth ornamented.

Depending on the quality of the art work, dyes, and fabric, the finest batik tulis halus cloth can fetch several thousand dollars and it probably took several months to make. Batik tulis has both sides of the cloth ornamented.

In Indonesia, traditionally, batik was sold in 2.25-meter lengths used for kain panjang or sarong for kebaya dress. It can also be worn by wrapping it around the body, or made into a hat known as blangkon. Infants are carried in batik slings decorated with symbols designed to bring the child luck. Certain batik designs are reserved for brides and bridegrooms, as well as their families. The dead are shrouded in funerary batik.[1] Other designs are reserved for the Sultan and his family or their attendants. A person's rank could be determined by the pattern of the batik he or she wore.

For special occasions, batik was formerly decorated with gold leaf or dust. This cloth is known as prada (a Javanese word for gold) cloth. Gold decorated cloth is still made today; however, gold paint has replaced gold dust and leaf.

For special occasions, batik was formerly decorated with gold leaf or dust. This cloth is known as prada (a Javanese word for gold) cloth. Gold decorated cloth is still made today; however, gold paint has replaced gold dust and leaf.

Batik garments play a central role in certain rituals, such as the ceremonial casting of royal batik into a volcano. In the Javanese naloni mitoni "first pregnancy" ceremony, the mother-to-be is wrapped in seven layers of batik, wishing her good things. Batik is also prominent in the tedak siten ceremony when a child touches the earth for the first time. Batik is also part of the labuhan ceremony when people gather at a beach to throw their problems away into the sea.[10]

Contemporary batik, while owing much to the past, is markedly different from the more traditional and formal styles. For example, the artist may use etching, discharge dyeing, stencils, different tools for waxing and dyeing, wax recipes with different resist values and work with silk, cotton, wool, leather, paper or even wood and ceramics. The wide diversity of patterns reflects a variety of influences, ranging from Arabic calligraphy, European bouquets and Chinese phoenixes to Japanese cherry blossoms and Indian or Persian peacocks.[1]

In Indonesia, batik popularity has its up and downs. Historically it was essential for ceremonial costumes and it was worn as part of a kebaya dress, which was commonly worn every day. According to Professor Michael Hitchcock of the University of Chichester (UK), batik "has a strong political dimension. The batik shirt was invented as a formal non-Western shirt for men in Indonesia in the 1960s.[11] It waned from the 1960s onwards, because more and more women chose western clothes. However, batik clothing has revived somewhat in the 21st century, due to the effort of Indonesian fashion designers to innovate the kebaya by incorporating new colors, fabrics, and patterns. Batik is a fashion item for many young people in Indonesia, such as a shirt, dress, or scarf for casual wear. For a formal occasion, a kebaya is standard for women. It is also acceptable for men to wear batik in the office or as a replacement for jacket-and-tie at certain receptions.

The flight attendants of Indonesian, Singaporean, and Malaysian national airlines all wear batik in their uniform. Batik sarongs are also designed as wraps for casual beachwear.

In the southern of Thailand island of Koh Samui, batik is easily found in the form of the resort uniforms, or decorations at many places, and is also the locals casual wear in the forms of sarongs or shirts and blouses, and is the most common, or even one of the symbolic products for the ones whom travels to the Koh Samui Island. The Batik of Samui is mostly showing the beauty and attractions of the paradise island and its culture, such as the coconut shells, the beaches, palm trees, the islands tropical flowers, fishing boats, its rich water life and southern dancer, Papthalung.

The palace courts (keratonan) in two cities in central Java are known for preserving and fostering batik traditions:

Melted wax (Javanese: malam) is applied to cloth before being dipped in dye. It is common for people to use a mixture of beeswax and paraffin wax. The beeswax will hold to the fabric and the paraffin wax will allow cracking, which is a characteristic of batik. Wherever the wax has seeped through the fabric, the dye will not penetrate. Sometimes several colours are used, with a series of dyeing, drying and waxing steps.

Melted wax (Javanese: malam) is applied to cloth before being dipped in dye. It is common for people to use a mixture of beeswax and paraffin wax. The beeswax will hold to the fabric and the paraffin wax will allow cracking, which is a characteristic of batik. Wherever the wax has seeped through the fabric, the dye will not penetrate. Sometimes several colours are used, with a series of dyeing, drying and waxing steps.

Thin wax lines are made with a canting, a wooden handled tool with a tiny metal cup with a tiny spout, out of which the wax seeps. After the last dyeing, the fabric is hung up to dry. Then it is dipped in a solvent to dissolve the wax, or ironed between paper towels or newspapers to absorb the wax and reveal the deep rich colors and the fine crinkle lines that give batik its character. This traditional method of batik making is called batik tulis.

For batik prada, gold leaf was used in the Yogjakarta and Surakarta area. The Central Javanese used gold dust to decorate their prada cloth. It was applied to the fabric using a handmade glue consisting of egg white or linseed oil and yellow earth. The gold would remain on the cloth even after it had been washed. The gold could follow the design of the cloth or could take on its own design. Older batiks could be given a new look by applying gold to them.

The invention of the copper block (cap) developed by the Javanese in the 20th century revolutionized batik production. By block printing the wax onto the fabric, it became possible to mass-produce designs and intricate patterns much faster than one could possibly do by using a canting.

Batik print is the common name given to fabric that incorporates batik pattern without actually using the wax-resist dyeing technique. It represents a further step in the process of industrialization, reducing the cost of batik by mass-producing the pattern repetitively, as a standard practice employed in the worldwide textile industry.

Javanese traditional batik, especially from Yogyakarta and Surakarta, has special meanings rooted to the Javanese conceptualization of the universe. Traditional colours include indigo, dark brown, and white, which represent the three major Hindu Gods (Brahmā, Visnu, and Śiva). This is related to the fact that natural dyes are most commonly available in indigo and brown. Certain patterns can only be worn by nobility; traditionally, wider stripes or wavy lines of greater width indicated higher rank. Consequently, during Javanese ceremonies, one could determine the royal lineage of a person by the cloth he or she was wearing.

Other regions of Indonesia have their own unique patterns that normally take themes from everyday lives, incorporating patterns such as flowers, nature, animals, folklore or people. The colours of pesisir batik, from the coastal cities of northern Java, is especially vibrant, and it absorbs influence from the Javanese, Arab, Chinese and Dutch culture. In the colonial times pesisir batik was a favorite of the Peranakan Chinese, Dutch and Eurasians.[citation needed]

UNESCO designated Indonesian batik as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity on October 2, 2009. As part of the acknowledgment, UNESCO insisted that Indonesia preserve their heritage.[1]

Etymology

Although the word's origin is Javanese, its etymology may be either from the Javanese amba ('to write') and titik ('dot' or 'point'), or constructed from a hypothetical Proto-Austronesian root *beCík, meaning 'to tattoo' from the use of a needle in the process. The word is first recorded in English in the Encyclopædia Britannica of 1880, in which it is spelled battik. It is attested in the Indonesian Archipelago during the Dutch colonial period in various forms: mbatek, mbatik, batek and batik.[3][4][5][edit] History

Wax-resist dyed textile from Niya (Tarim Basin), China

In Java, Indonesia, batik predates written records. GP. Rouffaer argues that the technique might have been introduced during the 6th or 7th century from India or Sri Lanka.[6] On the other hand, JLA. Brandes (a Dutch archeologist) and F.A. Sutjipto (an Indonesian archeologist) believe Indonesian batik is a native tradition, regions such as Toraja, Flores, Halmahera, and Papua, which were not directly influenced by Hinduism and have an old age tradition of batik making.[7]

GP. Rouffaer also reported that the gringsing pattern was already known by the 12th century in Kediri, East Java. He concluded that such a delicate pattern could only be created by means of the canting (also spelled tjanting or tjunting; IPA: [tʃantɪŋ]) tool. He proposed that the canting was invented in Java around that time.[7]

Batik was mentioned in the 17th century Malay Annals. The legend goes when Laksamana Hang Nadim was ordered by Sultan Mahmud to sail to India to get 140 pieces of serasah cloth (batik) with 40 types of flowers depicted on each. Unable to find any that fulfilled the requirements explained to him, he made up his own. On his return unfortunately, his ship sank and he only managed to bring four pieces, earning displeasure from the Sultan.[8][9]

In Europe, the technique is described for the first time in the History of Java, published in London in 1817 by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles who had been a British governor for the island. In 1873 the Dutch merchant Van Rijckevorsel gave the pieces he collected during a trip to Indonesia to the ethnographic museum in Rotterdam. Today Tropenmuseum housed the biggest collection of Indonesian batik in the Netherlands. The Dutch were active in developing batik in the colonial era, they introduced new innovations and prints. And it was indeed starting from the early 19th century that the art of batik really grew finer and reached its golden period. Exposed to the Exposition Universelle at Paris in 1900, the Indonesian batik impressed the public and the artisans.[6] After the independence of Indonesia and the decline of the Dutch textile industry, the Dutch batik production was lost, the Gemeentemuseum, Den Haag contains artifacts from that era.

Due globalization and industrialization, which introduced automated techniques, new breeds of batik, known as batik cap (IPA: [tʃap]) and batik print emerged, and the traditional batik, which incorporates the hand written wax-resist dyeing technique is known now as batik tulis (lit: 'Written Batik'). At the same time Indonesian immigrants to Malaysia and Singapore brought Indonesian batik with them.

[edit] Culture

In one form or another, batik has worldwide popularity. Now, not only is batik used as a material to clothe the human body, its uses also include furnishing fabrics, heavy canvas wall hangings, tablecloths and household accessories. Batik techniques are used by famous artists to create batik paintings, which grace many homes and offices.[edit] Indonesia

The Javanese aristocrats R.A. Kartini in kebaya and her husband. Her skirt is of batik, with the parang pattern, which was for aristocrats. Her husband is wearing a blangkon

In Indonesia, traditionally, batik was sold in 2.25-meter lengths used for kain panjang or sarong for kebaya dress. It can also be worn by wrapping it around the body, or made into a hat known as blangkon. Infants are carried in batik slings decorated with symbols designed to bring the child luck. Certain batik designs are reserved for brides and bridegrooms, as well as their families. The dead are shrouded in funerary batik.[1] Other designs are reserved for the Sultan and his family or their attendants. A person's rank could be determined by the pattern of the batik he or she wore.

Sacred Dance of Bedhoyo Ketawang. The batik is wrapped around the body

Batik garments play a central role in certain rituals, such as the ceremonial casting of royal batik into a volcano. In the Javanese naloni mitoni "first pregnancy" ceremony, the mother-to-be is wrapped in seven layers of batik, wishing her good things. Batik is also prominent in the tedak siten ceremony when a child touches the earth for the first time. Batik is also part of the labuhan ceremony when people gather at a beach to throw their problems away into the sea.[10]

Contemporary batik, while owing much to the past, is markedly different from the more traditional and formal styles. For example, the artist may use etching, discharge dyeing, stencils, different tools for waxing and dyeing, wax recipes with different resist values and work with silk, cotton, wool, leather, paper or even wood and ceramics. The wide diversity of patterns reflects a variety of influences, ranging from Arabic calligraphy, European bouquets and Chinese phoenixes to Japanese cherry blossoms and Indian or Persian peacocks.[1]

In Indonesia, batik popularity has its up and downs. Historically it was essential for ceremonial costumes and it was worn as part of a kebaya dress, which was commonly worn every day. According to Professor Michael Hitchcock of the University of Chichester (UK), batik "has a strong political dimension. The batik shirt was invented as a formal non-Western shirt for men in Indonesia in the 1960s.[11] It waned from the 1960s onwards, because more and more women chose western clothes. However, batik clothing has revived somewhat in the 21st century, due to the effort of Indonesian fashion designers to innovate the kebaya by incorporating new colors, fabrics, and patterns. Batik is a fashion item for many young people in Indonesia, such as a shirt, dress, or scarf for casual wear. For a formal occasion, a kebaya is standard for women. It is also acceptable for men to wear batik in the office or as a replacement for jacket-and-tie at certain receptions.

[edit] Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, and Thailand

Batik is often worn in Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, and southern Thailand brought there by Indonesian immigrants or merchants in the 19th century. Malaysian batik can be found on the east cost of Malaysia such as Kelantan, Terengganu and Pahang, while batik in Johor clearly shows Javanese and Sumatran influences since there is a lot of Javanese and Sumatran immigrants in southern Malaysia. The most popular motifs are leaves and flowers. Malaysian batik never depicting humans or animals because Islamic norms forbid anthropomorph and animal images as decoration. However, the butterfly theme is a common exception. The Malaysian batik is also famous for its geometrical designs, such as spirals. The method of Malaysian batik making also quite different from those of Indonesian Javanese batik, the pattern is larger and simpler, it seldom or never uses canting to create intricate patterns and rely heavily on brush painting method to apply colors on fabrics. The colors also tends to be more light and vibrant than deep colored Javanese batik.The flight attendants of Indonesian, Singaporean, and Malaysian national airlines all wear batik in their uniform. Batik sarongs are also designed as wraps for casual beachwear.

In the southern of Thailand island of Koh Samui, batik is easily found in the form of the resort uniforms, or decorations at many places, and is also the locals casual wear in the forms of sarongs or shirts and blouses, and is the most common, or even one of the symbolic products for the ones whom travels to the Koh Samui Island. The Batik of Samui is mostly showing the beauty and attractions of the paradise island and its culture, such as the coconut shells, the beaches, palm trees, the islands tropical flowers, fishing boats, its rich water life and southern dancer, Papthalung.

[edit] Azerbaijan

The batik pattern can be found in its women's silk scarves, known as kelagai, which have been part of women's clothing there for centuries. Kelagai were first produced in the village of Basgal and were created using the stamping method and natural colors. The cocoons were traditionally processed by women while the hand-printing with hot wax was only entrusted to male artists. The silk spinning and production of kelagai in Azerbaijan slumped after the fall of the USSR. It was the Inkishaf Scientific Center that revived kelagai in the country. Kelagai is worn by women both old and young. Young women prefer bright colors, while older women wear dark colors.[12][edit] China

Batik is done by the ethnic people in Guizhou Province, in the South-West of China. The Miao, Bouyei and Gejia people use a dye resist method for their traditional costumes. The traditional costumes are made up of decorative fabrics, which they achieve by pattern weaving and wax resist. Almost all the Miao decorate hemp and cotton by applying hot wax then dipping the cloth in an indigo dye. The cloth is then used for skirts, panels on jackets, aprons and baby carriers. Like the Javanese, their traditional patterns also contain symbolism, the patterns include the dragon, phoenix, and flowers.[13][edit] Types and Variations of Batik

[edit] Javanese Kraton Batik (Javanese court Batik)

Javanese keraton (court) Batik is the oldest batik tradition known in Java. Also known as Batik Pedalaman (inland batik) in contrast with Batik Pesisiran (coastal batik). This type of batik has earthy color tones such as black, brown, and dark yellow (sogan), sometimes against a white background. The motifs of traditional court batik have symbolic meanings. Some designs are restricted: larger motifs can only be worn by royalty; and certain motifs are not suitable for women, or for specific occasions (e.g., weddings).The palace courts (keratonan) in two cities in central Java are known for preserving and fostering batik traditions:

- Surakarta (Solo City) Batik. Traditional Surakarta court batik is preserved and fostered by the Susuhunan and Mangkunegaran courts. The main areas that produce Solo batik are the Laweyan and Kauman districts of the city. Solo batik typically has sogan as the background color. Pasar Klewer near the Susuhunan palace is a retail trade center.

- Yogyakarta Batik. Traditional Yogya batik is preserved and fostered by the Yogyakarta Sultanate and the Pakualaman court. Usually Yogya Batik has white as the background color. Fine batik is produced at Kampung Taman district. Beringharjo market near Malioboro street is well known as a retail batik trade center in Yogyakarta.

[edit] Pesisir Batik (Coastal Batik)

Pesisir batik is created and produced by several areas on the northern coast of Java and on Madura. As a consequence of maritime trading, the Pesisir batik tradition was more open to foreign influences in textile design, coloring, and motifs, in contrast to inland batik, which was relatively independent of outside influences. For example, Pesisir batik utilizes vivid colors and Chinese motifs such as clouds, phoenix, dragon, qilin, lotus, peony, and floral patterns.- Pekalongan Batik. The most famous Pesisir Batik production area is the town of Pekalongan in Central Java province. Compared to other pesisir batik production centers, the batik production houses in this town is the most thriving. Batik Pekalongan was influenced by both Dutch-European and Chinese motifs, for example the buketan motifs was influenced by European flower bouquet.

- Cirebon Batik. Also known as Trusmi Batik because that is the primary production area. The most well known Cirebon batik motif is megamendung (rain cloud) that was used in the former Cirebon kraton. This cloud motif shows Chinese influence.

- Lasem Batik. Lasem batik is characterized by a bright red color called abang getih pithik (chicken blood red). Batik Lasem is heavily influenced by Chinese culture.

- Tuban Batik. Batik gedog is the speciality of Tuban Batik, the batik was created from handmade tenun (woven) fabrics.

- Madura Batik. Madurese Batik displays vibrant colors, such as yellow, red, and green. Madura unique motifs for example pucuk tombak (spear tips), also various flora and fauna images.

[edit] Indonesian Batik from other areas

[edit] Java

- Priangan Batik or Sundanese Batik is the term proposed to identify various batik cloths produced in the "Priangan" region, a cultural region in West Java and Northwest Java (Banten).[14] Traditionally this type of batik is produced by Sundanese people in the several district of West Java such as Ciamis, Garut, an Tasikmalaya; however it also encompasses Kuningan Batik which demonstrate Cirebon Batik influences, and also Banten Batik that developed quite independently and have its own unique motifs. The motifs of Priangan batik are visually naturalistic and strongly inspired by flora (flowers and swirling plants) and fauna (birds especially peacock and butterfly). The variants and production centers of Priangan Batik are:

- Ciamis Batik. Ciamis used to rival other leading batik industry centers in Java during early 20th century. Compared to other regions, Ciamis batik is stylistically less complex. The flora and fauna motifs known as ciamisan are drawn in black, white, and yellowish brown. Motifs are similar to coastal Cirebon Batik, but the thickness of coloring share the same styles as inland batik. The thick coloring of Ciamis batik is called sarian.

- Garut Batik. This type of batik is produced in the Garut district of West Java. Garutan batik can be identified by its distinctive colors, gumading (yellowish ivory), indigo, dark red, dark green, yellowish brown, and purple. Ivory stays dominant in the background. Despite applying traditional Javanese court motifs such as rereng, Garut batik uses lighter and brighter colors compared to Javanese court batik.

- Tasikmalaya Batik. This type of batik is produced in the Tasikmalaya district, West Java. Tasikmalaya Batik has its own traditional motif such as umbrella. Center of Tasikmalaya Batik can be found in Ciroyom District about 2 km from city center of Tasikmalaya.

- Kuningan Batik.

- Banten Batik. This type of batik employs bright and soft pastel colors. It represents a revival of a lost art from the Sultanate of Banten, rediscovered through archaeological work during 2002-2004. Twelve motifs from locations such as Surosowan and several other places have been identified.[15]

- Java Hokokai Batik. This type is characterized by flowers in a garden surrounded by butterflies. This motif originated during the Japanese occupation of Java in the early 1940s.

[edit] Bali

- Balinese Batik. Balinese batik was influenced by neighbouring Javanese Batik and is relatively recent compared to the latter island, having been stimulated by the tourism industry and consequent rising demand for souvenirs (since the early 20th century). In addition to the traditional wax-resist dye technique and industrial techniques such as the stamp (cap) and painting, Balinese batik sometimes utilizes ikat (tie dye). Balinese batik is characterized by bright and vibrant colors, which the tie dye technique blends into a smooth gradation of color with many shades.

[edit] Sumatra

- Jambi Batik. Trade relations between the Melayu Kingdom in Jambi and Javanese coastal cities have thrived since the 13th century. Therefore, the northern coastal areas of Java (Cirebon, Lasem, Tuban, and Madura) probably influenced Jambi in regard to batik. In 1875, Haji Mahibat from Central Java revived the declining batik industry in Jambi. The village of Mudung Laut in Pelayangan district is known for producing Jambi batik. This Jambi batik, as well as Javanese batik, influenced the batik craft in the Malay peninsula.[16]

- Aceh Batik.

- Palembang Batik.

- Riau Batik.

[edit] Modern

Out of its traditional context, batik can also be as a medium for artists to make modern paintings or art. Such arts can be categorized in the normal categorization of arts of the west.| Sydney Opera House (Artist - Arman Mamyan) |

[edit] Batik Collectors

- Santosa Doellah has been recognised by The Indonesian Museum of Records as having the world’s largest collector of ancient Chinese-influenced Indonesian batik textiles. In total his collection are about 10,000 batik pieces.[17]

- The late mother of United States president Barack Obama, Ann Dunham was an avid collector of Batik. In 2009, an exhibition of Dunham's textile batik art collection (A Lady Found a Culture in its Cloth: Barack Obama's Mother and Indonesian Batiks) toured six museums in the United States, finishing the tour at the Textile Museum.[18]

- Nelson Mandela wears a batik shirt on formal occasions, the South Africans call it a Madiba shirt.

[edit] Technique

A Batik Tulis maker applying melted wax following pattern on fabric using canting, Yogyakarta (city), Indonesia.

Thin wax lines are made with a canting, a wooden handled tool with a tiny metal cup with a tiny spout, out of which the wax seeps. After the last dyeing, the fabric is hung up to dry. Then it is dipped in a solvent to dissolve the wax, or ironed between paper towels or newspapers to absorb the wax and reveal the deep rich colors and the fine crinkle lines that give batik its character. This traditional method of batik making is called batik tulis.

For batik prada, gold leaf was used in the Yogjakarta and Surakarta area. The Central Javanese used gold dust to decorate their prada cloth. It was applied to the fabric using a handmade glue consisting of egg white or linseed oil and yellow earth. The gold would remain on the cloth even after it had been washed. The gold could follow the design of the cloth or could take on its own design. Older batiks could be given a new look by applying gold to them.

[edit] Industrialization of Technique

The application of wax with a canting is done with great care and therefore is very time-consuming. As the population increased and commercial demand rose, time-saving methods evolved. Other methods of applying the wax to the fabric include pouring the liquid wax, painting the wax with a brush, and putting hot wax onto pre-carved wooden or copper block (called a cap or tjap) and stamping the fabric.The invention of the copper block (cap) developed by the Javanese in the 20th century revolutionized batik production. By block printing the wax onto the fabric, it became possible to mass-produce designs and intricate patterns much faster than one could possibly do by using a canting.

Batik print is the common name given to fabric that incorporates batik pattern without actually using the wax-resist dyeing technique. It represents a further step in the process of industrialization, reducing the cost of batik by mass-producing the pattern repetitively, as a standard practice employed in the worldwide textile industry.

Tunggu Aku, Sebentar Saja

Badan Satria tergadah menghadap ke atas langit, memandangi langit luas tanpa menjangkau ujung-ujungnya. Kemudian, ia kembali memandangi sebuah foto kecil berukuran dompet dari tangan kirinya. Perlahan ia mengelus-elus benda itu sembari tersenyum.

Di dalam foto itu terdapat sejuta kenangan indah yang mengendap, bak bukit kapur yang terkena sedimentasi. Satria sedang tersenyum bersama seorang gadis yang amatcantik di sampingnya. Rambutnya hitam pekat berkilauan serta kedua matanya yang cukup sipit. Si gadis juga ikut tersenyum riang bersamanya.

Sebuah foto yang diabadikan dua tahun lalu, ketika ulang tahun Laura yang ke 20. Satria datang membawa sebuah kado, berupa sweater lengkap beserta syal putih tebalnya. Dan di foto itu, Laura tersenyum manis sambil memegangi syal yang melilit di lehernya. Itu adalah yang pertama kali dan terakhir kalinya bagi Satya melihat sang pujaan hatinya memakai benda pemberiannya.

Karena semenjak enam bulan lalu hubungan mereka berakhir. Laura yang memintanya untuk putus dengan alasan ia sudah tidak ada persaan apa-apa lagi pada Satria. Namun, Satria masih harus memutar otaknya karena ia pikir itu bukanlah alasan yang utama, mengingat Laura adalah seorang gadis yang sangat tulus dan tidak ahli dalam berkamuflase.

Semenjak berpisah tak ada lagi senyuman dari bibir mungilnya, tak ada lagi suara-suara merdu yang melintasi telinga Satria. Dua hal yang terlalu indah dari Laura, hingga Satria tak bisa melupakannya walau setitik bayangannnya saja. Yang paling menyakitkan bagi Satria adalah ketika melihat Laura begitu cepat memilih orang lain untuk menggantikan posisinya. Laura juga tak lagi pernah menganggapnya ada, walau itu hanya sebatas teman belaka.

Satria seperti musuh baginya. Tapi, di balik itu semua, sakithati Satria selalu dapat ditutupi oleh rasa cintanya yang terlanjur membukit. Ia bertekad, bagaimanapun Laura memperlakukannya sekarang atau nanti, ia akan tetap menjadi Satria yang dulu tanpa kebencian sedikitpun.

******

Motor bebek Satria mulai berpacu di suasana pagi yang masih sangat basah. Lantas ia segera berangkat ke suatu tempat yang biasa ia datangi tiap pagi. Sebuah jalan dipinggir kota

Namun terkadang, ia juga harus menahan sakit hati saat melihat laura bersama pria lain melintas di hadapannya. Ia akan menunduk dan segera berlalu.

******

Jalanan mulai sepi, senja datang perlahan mengusik kekuasaan matahari. Satria bangun dari posisinya yamg sejka tadi merebahkan diri di tanah. Sejenak ia merenggangkan otot-otot punggungnya yang dirasa kaku. Udara mulai dingin dan pandangan mata tak sejelas tadi.

Sambil membenarkan duduknya di sepeda, secara kebetulan sesuatu yang ia pikirkan sejak tadi muncul. Kemunculan laura bersama pria lain semakin membuat Satria patah arah. Satria berpura-pura tidak mengetahui keberadaan mereka, ia cepat-cepat berlalu dari tempat itu. Betapa sangat jelas kemesraan yang ditunjukkan Laura kepada Gio, pacar barunya. Dan betapa keras pula hatinya tak dapat mersakan penderitaan Satria selama ini.

Laura bisa tertawalebar di hadapan Gio,namun tak sudi sedetikpun untuk membagi senyumnya untuk Satria. Mungkinkah Laura sekarang sangat membencinya? Hanya Laura sendiri dan Tuhan yang tahu.

******

“Sat, jangan ke sana

“Emang di kelas ada apa?” Tanya Satria penasaran.

“Pokoknya jangan masuk dulu deh, nanti malah nyesel !” ujar Lanny meyakinkan Satria.

Satria tidak memperdulikan larangan Lanny, ia menjadi tambah penasaran. Ia melangkah seenaknya hingga memecahkan pot bunga di sepan kelas, semua penghuni kelas sontak kaget. Rupanya di dalam ada Laura bersama Gio tengah bercanda.

Semua mata tertuju pada Satria yang tertegun, ia bingung dan salah tingkah. Apalagi ia dibuat cemburu berat karena pemandangan barusan, semakin membuatnya gelisah bukan makin. Kemudian ia berusaha berlari menjauhi kelas, namun lengannya berhasil di jangkau oleh Laura.

“Kamu mau ke mana?” Tanya Laura dengan tatapan sedingin es.

“Aku…aku mau pergika kantin” jawab Satria gugup.

“Kenapa kamu lari? Kamu liat aku sama Gio seperti ngeliat hantu aja!!!”

“Nggak bukan begitu, aku Cuma...” kalimat Satria menggantung

(Satria berupaya mengalihkan perhatian Laura dengan memungut sebuah buku di lantai)

“Ini, aku cari buku ini” jelas Satria tertatih

(Berupaya menahan genangan air matanya yang sejak tadi ingin ditumpahkan)

Satria langsung pergi meninggalkan Laura yang tertegun

******

Handphone Satria berdering, sebuah pesan masuk dari seseotang yang diberinya nama “Harapanku”

Dari : Harapanku

“Tolong berhenti brharap sama aku, aku sdh gak punya prasaan apa2 lg sama kamu. Karena skrg aku udah punya Gio. Lupakan semuanya”. Satria mengerutkan keningnya. Lagi-lagi ia harus sakit hati.

Namun, Satria lebih memilih diam dalm keterpurukannya. Ia masih tetap berharap ada celah yang mungkin bisa dioerbaiki dari hubungannya bersama Laura.

******

Satria menemui Lanny, sahabat baiknya. Ia butuh seseorang untuk mendengar segala keluh kesahnya.

“Gimana ini Lanny?” Tanya Satria putus asa.

“Maksud kamu hubungan kamu sama si Laura?”

“Iya, aku bingung sama keadaan. Sekarang Laura benci banget sama aku, gimana mau balikan kalo begini?”

“Hmmm mungkin itu udah yang terbaik buat kalian berdua. Kalo memang udah ditakdirkan berpisah mau apalagi”

“Gak semudah itu Lanny!!!”

“Kamu yang penting ikhlas Satria,kalo dia emang jodohsama kamu. Dia gak akan pergi keman-mana kok”

Satria menggelang-gelengkan kepalanya, ia semakin merasa dipersulit keadaan. Melupakan Laura adalah hal tersulit baginya.

******

Satu per satu kotak keramik dilalui oleh gerak kaki Satria yang putus asa. Setelah dari Lanny, ia seperti bertambah gila. Semakin ia berusaha lupa tentang Laura, wajah cantiknya selalu muncul di benaknya dengan sangat jelas. Tanpa ia sadari telah tiba di depan kelas. Perlahan ia mengangkat kepalanya yang daritadi menunduk.

Suasana kelas cukup ramai, tapi Satria enggan lekas masuk karena ada Laura di dalam yang melihatnya tajam. Satria melanjutkan langkahnya bermaksud meninggalkan kelas, namun Lanny yang baru saja tiba menarik lengan kirinya.

“Loh Sat, mau kemana?” Tanya Lanny.

“Oh mau jalan-jalan sebentar”

“Gimana sih ! Bentar lagi kan

(dengan ekspresi seperti polisi sewaktu menilang pengendara motor)

“Oh gitu ya..” jawab Satria pasrah

“Yuk”

(Menarik paksa tubuh Satria agar lekas masuk kelas)

Di kelas, Lanny duduk berdampingan dengan Laura dan Satria tepat berada di belakangnya. Mereka bertiga diam seribu bahasa, suasana baru cair ketika Lanny mengajak Satria bercanda sampai tertawa cekikikan. Meski sangat dekat, Satria sungkan untuk menatap ke arah Laura.

Ia khawatir nantinya Laura akan memalingkan wajahnya dan pindah temapt duduk. Akhirnya jam kuliah usai, Satria membenahi buku-bukunya dengan cepat dan segera menuju pintu.

“Sat, kok buru-buru? Gak mau pulang bareng?” Tanya Lanny

“Maaf Lan, aku masih ada urusan. Kamu pulang sama…”

(Mengisyaratkan Lanny bahwa ia bisa apulang bersama Laura)

“Laura, kamu sekarang mau gak pulang sama aku?” pinta Lanny

“Maaf Lan, aku dijemput Gio”

“Oh iya deh, gak apa-apa kalo kalian pada gak bisa. Aku bisa pulang sendiri, hehehe”

(Laura dan Satria tersenyum kecut pada Lanny)

******

Satria sebenarnya berbohong, ia tak punya urusan apa-apa setalh jam kuliah usai. Hanya saja ia tak ingin lama-lama berhadapan dengan Laura, maka persaannya akan campur aduk. Ia hanya berjalan pelan mengitari seluruh kampus, tanpa sadar ia kembali ke tampatnya semula. Ia kembali berada di depan kelas. Karena suasana kampus sudah mulai sepi, suara-suara kecil mudah terdengar.

Tiba-tiba suara kursi terjatuh terdengar dari kelasnya, Satria kaget dan mengintipnya dari balik pintu. Ternyata Laura yang menjatuhkan kursi itu, entah apa yang ia lakukan sendirian di sana

Satria hanya tertegun di tempat persembunyiannya.

******

“Hallo Lanny?” Tanya Satria lewat telpon

“Iya Sat, kenpa?”

“Kamu tahu gak Laura sakit apa? Tadi aku ketemu dia seperti orang mau pingsan!”

“Hmmm mungkin kecapean aja kali, aku juga gak tahu. Coba deh Tanya sendiri” usul Lanny

“Ah gak mungkin, dia mana mau ngomong sama aku. Ya udah, makasih ya”

“Oke”

******

Dengan persaannya yang sangat khawatir, Satria masih menyempatkan diri untuk menjenguk salah satu temannya yang dirawat di rumah sakit. Dan lagi-lagi ia bertemu Laura dan Gio, namun kali ini mereka berada di salah satu ruang dokter. Satria memperhatikannya dari luar. Matanya terbelalak saat tahu kalau Laura di dalam sana

Tak bisa dibohongi jika hatinya merasa sangat bahagia ketika Laura mengenakan benda pemberiannya.

“Laura, kamu sakit apa?”

(Laura shock melihat Satria tiba-tiba berada di hadapannya)

“Aku gak sakit kok!” ucapnya ketus sambil meninggalkan Satria yang masih heran.

******

Satu minggu kemudian, Laura tidak masuk kuliah. Dan itu berlanjut hingga minggu-minggu berikutnya. Tidak ada yang tahu secara pasti keberadaannya. Satria juga tak pernah melihat Laura di jalan yang biasa ia lewati selama ini. Di tengah lamunannya tentang keberadaan Laura, sebuah panggilan tak dikenal dari seseorang.

“Ini Satria?”

“Bener, di sini Satria”

“Tolong ke sini sekarang juga ya, ntar alamatnya aku kirim sebentar lagi”

Siapakah dia? Membatin Satria.

Suara seorang lelaki yang terdengar sangat khawatir, tak lama kemudian Satria beranjak menuju ke sebuah alamat yang dikirimkan untuknya. Ternyata alamat itu adalah sebuah rumah sakit umum.

Satria kebingungan sendiri di lobby rumah sakit, kemudian Gio datang menghampirinya.

“Ada

(Ekspresi wajahnya langsung berubah saat ditemui Gio)

“Siapa?” Tanya Satria dingin

“Ikut aku, kamu akan segera tahu”

Gio membawanya ke sebuah kamardan menyuruhnya segera masuk.

Rupanya di dalam sudah ada Laura yang terbaring sakit, wajahnya sangat pucat dan bedannya mulai kurus.

“Laura” sapa Satria heran

“Mendekat Satria” ucap laura setengah berbisik

“Kamu bilang kamu gak sakit kan

(Mulut Satria disentuh telunjuk Laura, tanda ia harus menghentikan pertanyaannya)

“Sat, bisa ambilin sayal putihku di kursi itu” pinta Laura sambil menunjuk ke arah kursi.

(Satria mengangguk dan segera mengambilkannya)

“Bisa pasangin di leherku?”

Syal itu dililitkan ke leher Laura dengan penuh perhatian oleh Satria.

“Apa kamu bisa jelasin ini semuanya laura?” Tanya Satria

Laura tak memperdulikan pertanyaan Satria, ia malah menarik lengan Satria agar mendekat, kemudia memelukanya sangat erat.

“Aku cinta kamu Satria” ujar Laura menangis

“Ada

“Aku mohon Satria, beri aku waktu sebentar saja buat ada di pelukan kamu. Biar aku tenang, biar aku punya semangat lagi untuk bisa lebih lama sama kamu”

Satria bertambah bingung bukan kepalang, tapi ia menuruti permintaan Laura untuk tidak mengungkit masalah itu sekarang.

******

Satria bermalam di rumah sakit, ia senang karena akhirnya Laura telah kembali ke sisinya. Namun ia juga khawatir dan bingung dengan keadaan yang berubah sedrastis ini. Laura akhirnya bisa tertawa lagi ketika berada di sisinya. Ini adalah sebuah malam yang sangat didambkanoleh Satria selama ini.

******

Pagi datang, malam melayang. Satria terbangun dari sofa yang dekat dengan kasur Laura berbaring. Kemudian ia tersadar jika Laura sudah tidak ada di sana

Ia histeris, lalu Gio datang menenangkannya dengan membawa sebuah surat

To : Satria

Satria, maaf, maaf, dan maaf. Mungkin belum cukup untuk buat kamu maafin aku. Maafkan aku karena selama ini sudah bikin kamu sakit hati. Mungkin dari awal harusnya aku bilang kalau aku sedang sakit, makakejadiaannya gak akan serumit ini. Aku cuman gak ingin orang yang sayang sama aku jadi kasihan kalo tahu aku sedang sakit parah. Selama enam bulan berpisah aku berupaya untuk bikin kamu membenci aku dan melupakan aku Sat. Tapi aku salah menyangka bagaimana rasa cinta kamu sama aku. Kamu tetapperlakukan aku seperti dulu meski aku selalu berlaku buruk. Kamu tetap menjaga aku meski dari jauh, kamu tetap khawatir meski aku selalu bikin kamu sakit hati. Selama ini aku tak mengerti Sat, tapi perlahan aku mencoba untuk memahaminya. Memahami saat kamu berlinang air mata ketika melihatku mesra dengan Gio, memahami bagaimana khawatirnya kamu saat melihatku hampir pingsan di kelas. Dan memahami seberapa besar cinta kamu buat aku. Mungkin saat kamu baca suratku ini, aku sudah tak berda di sana surat

Laura

Nama : riza afita surya

Kelas : xii apa 5/25

Bali[3] was inhabited by about 2000 BC by Austronesian peoples who migrated originally from Taiwan through Maritime Southeast Asia.[4] Culturally and linguistically, the Balinese are thus closely related to the peoples of the Indonesian archipelago, the Philippines, and Oceania.[5] Stone tools dating from this time have been found near the village of Cekik in the island's west.[6]

Balinese culture was strongly influenced by Indian and Chinese, and particularly Hindu culture, in a process beginning around the 1st century AD. The name Bali dwipa ("Bali island") has been discovered from various inscriptions, including the Blanjong pillar inscription written by Sri Kesari Warmadewa in 914 AD and mentioning "Walidwipa". It was during this time that the complex irrigation system subak was developed to grow rice. Some religious and cultural traditions still in existence today can be traced back to this period. The Hindu Majapahit Empire (1293–1520 AD) on eastern Java founded a Balinese colony in 1343. When the empire declined, there was an exodus of intellectuals, artists, priests and musicians from Java to Bali in the 15th century.

Tanah Lot, one of the major temples in Bali

The first European contact with Bali is thought to have been made in 1585 when a Portuguese ship foundered off the Bukit Peninsula and left a few Portuguese in the service of Dewa Agung[7]. In 1597 the Dutch explorer Cornelis de Houtman arrives to Bali and, with the establishment of the Duch East India Company in 1602, the stage is set for colonial control two and a half centuries later when Dutch control expanded across the Indonesian archipelago throughout the second half of the nineteenth century (see Dutch East Indies). Dutch political and economic control over Bali began in the 1840s on the island's north coast, when the Dutch pitted various distrustful Balinese realms against each other.[8] In the late 1890s, struggles between Balinese kingdoms in the island's south were exploited by the Dutch to increase their control.

The Dutch mounted large naval and ground assaults at the Sanur region in 1906 and were met by the thousands of members of the royal family and their followers who fought against the superior Dutch force in a suicidal puputan defensive assault rather than face the humiliation of surrender.[8] Despite Dutch demands for surrender, an estimated 1,000 Balinese marched to their death against the invaders.[9] In the Dutch intervention in Bali (1908), a similar massacre occurred in the face of a Dutch assault in Klungkung. Afterwards the Dutch governors were able to exercise administrative control over the island, but local control over religion and culture generally remained intact. Dutch rule over Bali came later and was never as well established as in other parts of Indonesia such as Java and Maluku.

In the 1930s, anthropologists Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson, and artists Miguel Covarrubias and Walter Spies, and musicologist Colin McPhee created a western image of Bali as "an enchanted land of aesthetes at peace with themselves and nature", and western tourism first developed on the island.[10]

Balinese dancers show for tourists, Ubud.

Imperial Japan occupied Bali during World War II, during which time a Balinese military officer, Gusti Ngurah Rai, formed a Balinese 'freedom army'. The lack of institutional changes from the time of Dutch rule however, and the harshness of war requisitions made Japanese rule little better than the Dutch one.[11] Following Japan's Pacific surrender in August 1945, the Dutch promptly returned to Indonesia, including Bali, immediately to reinstate their pre-war colonial administration. This was resisted by the Balinese rebels now using Japanese weapons. On 20 November 1946, the Battle of Marga was fought in Tabanan in central Bali. Colonel I Gusti Ngurah Rai, by then 29 years old, finally rallied his forces in east Bali at Marga Rana, where they made a suicide attack on the heavily armed Dutch. The Balinese battalion was entirely wiped out, breaking the last thread of Balinese military resistance. In 1946 the Dutch constituted Bali as one of the 13 administrative districts of the newly-proclaimed State of East Indonesia, a rival state to the Republic of Indonesia which was proclaimed and headed by Sukarno and Hatta. Bali was included in the "Republic of the United States of Indonesia" when the Netherlands recognised Indonesian independence on 29 December 1949.

The 1963 eruption of Mount Agung killed thousands, created economic havoc and forced many displaced Balinese to be transmigrated to other parts of Indonesia. Mirroring the widening of social divisions across Indonesia in the 1950s and early 1960s, Bali saw conflict between supporters of the traditional caste system, and those rejecting these traditional values. Politically, this was represented by opposing supporters of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) and the Indonesian Nationalist Party (PNI), with tensions and ill-feeling further increased by the PKI's land reform programs.[8] An attempted coup in Jakarta was put down by forces led by General Suharto. The army became the dominant power as it instigated a violent anti-communist purge, in which the army blamed the PKI for the coup. Most estimates suggest that at least 500,000 people were killed across Indonesia, with an estimated 80,000 killed in Bali, equivalent to 5% of the island's population.[12] With no Islamic forces involved as in Java and Sumatra, upper-caste PNI landlords led the extermination of PKI members.[13]

As a result of the 1965/66 upheavals, Suharto was able to maneuver Sukarno out of the presidency, and his "New Order" government reestablished relations with western countries. The pre-War Bali as "paradise" was revived in a modern form, and the resulting large growth in tourism has led to a dramatic increase in Balinese standards of living and significant foreign exchange earned for the country.[8] A bombing in 2002 by militant Islamists in the tourist area of Kuta killed 202 people, mostly foreigners. This attack, and another in 2005, severely affected tourism, bringing much economic hardship to the island.

Balinese culture was strongly influenced by Indian and Chinese, and particularly Hindu culture, in a process beginning around the 1st century AD. The name Bali dwipa ("Bali island") has been discovered from various inscriptions, including the Blanjong pillar inscription written by Sri Kesari Warmadewa in 914 AD and mentioning "Walidwipa". It was during this time that the complex irrigation system subak was developed to grow rice. Some religious and cultural traditions still in existence today can be traced back to this period. The Hindu Majapahit Empire (1293–1520 AD) on eastern Java founded a Balinese colony in 1343. When the empire declined, there was an exodus of intellectuals, artists, priests and musicians from Java to Bali in the 15th century.

Tanah Lot, one of the major temples in Bali

The first European contact with Bali is thought to have been made in 1585 when a Portuguese ship foundered off the Bukit Peninsula and left a few Portuguese in the service of Dewa Agung[7]. In 1597 the Dutch explorer Cornelis de Houtman arrives to Bali and, with the establishment of the Duch East India Company in 1602, the stage is set for colonial control two and a half centuries later when Dutch control expanded across the Indonesian archipelago throughout the second half of the nineteenth century (see Dutch East Indies). Dutch political and economic control over Bali began in the 1840s on the island's north coast, when the Dutch pitted various distrustful Balinese realms against each other.[8] In the late 1890s, struggles between Balinese kingdoms in the island's south were exploited by the Dutch to increase their control.

The Dutch mounted large naval and ground assaults at the Sanur region in 1906 and were met by the thousands of members of the royal family and their followers who fought against the superior Dutch force in a suicidal puputan defensive assault rather than face the humiliation of surrender.[8] Despite Dutch demands for surrender, an estimated 1,000 Balinese marched to their death against the invaders.[9] In the Dutch intervention in Bali (1908), a similar massacre occurred in the face of a Dutch assault in Klungkung. Afterwards the Dutch governors were able to exercise administrative control over the island, but local control over religion and culture generally remained intact. Dutch rule over Bali came later and was never as well established as in other parts of Indonesia such as Java and Maluku.

In the 1930s, anthropologists Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson, and artists Miguel Covarrubias and Walter Spies, and musicologist Colin McPhee created a western image of Bali as "an enchanted land of aesthetes at peace with themselves and nature", and western tourism first developed on the island.[10]

Balinese dancers show for tourists, Ubud.

Imperial Japan occupied Bali during World War II, during which time a Balinese military officer, Gusti Ngurah Rai, formed a Balinese 'freedom army'. The lack of institutional changes from the time of Dutch rule however, and the harshness of war requisitions made Japanese rule little better than the Dutch one.[11] Following Japan's Pacific surrender in August 1945, the Dutch promptly returned to Indonesia, including Bali, immediately to reinstate their pre-war colonial administration. This was resisted by the Balinese rebels now using Japanese weapons. On 20 November 1946, the Battle of Marga was fought in Tabanan in central Bali. Colonel I Gusti Ngurah Rai, by then 29 years old, finally rallied his forces in east Bali at Marga Rana, where they made a suicide attack on the heavily armed Dutch. The Balinese battalion was entirely wiped out, breaking the last thread of Balinese military resistance. In 1946 the Dutch constituted Bali as one of the 13 administrative districts of the newly-proclaimed State of East Indonesia, a rival state to the Republic of Indonesia which was proclaimed and headed by Sukarno and Hatta. Bali was included in the "Republic of the United States of Indonesia" when the Netherlands recognised Indonesian independence on 29 December 1949.

The 1963 eruption of Mount Agung killed thousands, created economic havoc and forced many displaced Balinese to be transmigrated to other parts of Indonesia. Mirroring the widening of social divisions across Indonesia in the 1950s and early 1960s, Bali saw conflict between supporters of the traditional caste system, and those rejecting these traditional values. Politically, this was represented by opposing supporters of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) and the Indonesian Nationalist Party (PNI), with tensions and ill-feeling further increased by the PKI's land reform programs.[8] An attempted coup in Jakarta was put down by forces led by General Suharto. The army became the dominant power as it instigated a violent anti-communist purge, in which the army blamed the PKI for the coup. Most estimates suggest that at least 500,000 people were killed across Indonesia, with an estimated 80,000 killed in Bali, equivalent to 5% of the island's population.[12] With no Islamic forces involved as in Java and Sumatra, upper-caste PNI landlords led the extermination of PKI members.[13]

As a result of the 1965/66 upheavals, Suharto was able to maneuver Sukarno out of the presidency, and his "New Order" government reestablished relations with western countries. The pre-War Bali as "paradise" was revived in a modern form, and the resulting large growth in tourism has led to a dramatic increase in Balinese standards of living and significant foreign exchange earned for the country.[8] A bombing in 2002 by militant Islamists in the tourist area of Kuta killed 202 people, mostly foreigners. This attack, and another in 2005, severely affected tourism, bringing much economic hardship to the island.

Reog is a traditional Indonesian dance form. There are many type of Reogs in Indonesia, but the most famous one is Reog Ponorogo.

Reog Ponorogo tells the story of a battle between the King of Ponorogo and the magical lion Singa Barong. It usually consists of three sets of dances; each dance is performed by several dancers. The first dance is the opening dance, performed by male dancers wearing black costumes. The second dance is the Jaran Kepang dance; it is performed by female dancers wearing colourful costumes. The third dance is the main attraction of the show; it is performed by all the Reog dancers. The main male dancer, wearing a large and heavy lion mask, dances in the centre of the stage while the other dancers dance around him.

Reog dancers traditionally perform in a trance state.

Reog Ponorogo tells the story of a battle between the King of Ponorogo and the magical lion Singa Barong. It usually consists of three sets of dances; each dance is performed by several dancers. The first dance is the opening dance, performed by male dancers wearing black costumes. The second dance is the Jaran Kepang dance; it is performed by female dancers wearing colourful costumes. The third dance is the main attraction of the show; it is performed by all the Reog dancers. The main male dancer, wearing a large and heavy lion mask, dances in the centre of the stage while the other dancers dance around him.

Reog dancers traditionally perform in a trance state.

Kuda Lumping also called "Jaran Kepang" is a traditional Javanese dance depicting a group of horsemen. The dance employs a horse made from woven bamboo and decorated with colorful paints and cloth. Common Kuda Lumping dance only performed the dance of the troops riding horses, however another type of Kuda Lumping performance also incorporated trance and magic trick. When the "possessed" dancer is performing the dance in trance conditions, they can display unusual abilities, such as eating glass and resistance of whipping. Jaran kepang is also a part of Reog dance performance. Although this dance is native to Java, Indonesia, it also performed by Javanese immigrants in Suriname, Malaysia and Singapore.

Total Tayangan Halaman

Cari Blog Ini

Mengenai Saya

Labels

Blog archive

- Maret 2019 (1)

- November 2017 (6)

- Oktober 2017 (1)

- Juli 2017 (3)

- Mei 2013 (3)

- Desember 2012 (1)

- Mei 2012 (1)

- Maret 2012 (3)

- Februari 2012 (13)

- Januari 2012 (17)

- Desember 2011 (8)

- November 2011 (15)

- Oktober 2011 (1)

- September 2011 (1)

- Juli 2011 (8)

- April 2011 (2)

- Maret 2011 (1)

- Desember 2010 (1)

- Oktober 2010 (7)

- September 2010 (1)

- Agustus 2010 (10)

- Juli 2010 (2)

- Juni 2010 (1)

- Mei 2010 (2)

- November 2009 (2)

Powered by WordPress

©

Rubrik Riza - Designed by Matt, Blogger templates by Blog and Web.

Powered by Blogger.

Powered by Blogger.